posted by the Judge

Not sure if Santa's going to be reading this one, with all the stuff's he's got to go through, but here's our Sunday review: Ian Chung takes a nice long look at Afric McGlinchey's The Lucky Star of Hidden Things.

Take a nice long look at his review, via the above link.

Have a fantastic New Year's, and end it the way you began the day. (That would be: lying down. If you began it by doing something else, then by all means do something else).

Sunday 30 December 2012

Wednesday 26 December 2012

The Next Big Thing

I’ve been tagged by the very talented Melissa Lee-Houghton to give this interview for an expanding blog project called The Next Big Thing. You can read her interview here.

The idea is I post mine and tag other writers to do the same on 2 January 2013.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The title for Never Never Never Come Back came from the Al Stewart song 'Night Train to Munich', which adopts the voice of a senior agent instructing their colleague on an operation from which they may not return. I wanted my first collection to have the combination of paranoia and loneliness that plague the classic spy figure; distrusting everyone, under pressure to deliver something valuable without knowing why.

What genre does your book fall under?

Poetry

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Many of them are actually based on films and programmes anyway - 'Supper' focuses on a scene from Soylent Green, 'Yokohama Shopping' on the anime series of the same name and 'Schoolgirl Shootout' on the tragic lighthouse blitz in Japanese thriller Battle Royale. Maybe Tilda Swinton for the metal ex-assassin in 'Roy'. I'd quite like to see Rutger Hauer play Armin Meiwes. Cillian Murphy would take on the more lovelorn, gawky characters, while the main role in 'On coming out to your parents dressed as Dracula' could only go to Sam Rockwell. I love that man.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Wheeling a broken bike through an embarrassing dream in which nobody else is naked, nobody else has forgotten their gift and everyone else knows the words to the song

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Very hard to tell, though I think only one of the poems ('Splitting the ego with Mary') was more than two years old when we put NNNCB together. Most of the poems came from NaPoWriMo 2011 and 2012, which tends to dust under the corners of the brain where the weird stuff lies. The putting together and sifting of the poems took about six months with editor Roddy Lumsden.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Everybody is under pressure to fulfill multiple roles at once, relating to this idea of a person they're advised to become. I wanted to probe the idea of breaking down under this brick-filled rucksack, of the ludicrous rules that can quietly destroy people. Poetry, with its restrictions, concentration of language, repetitions and cycles, seemed like the best form in which to explore this.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

A good helping of robots and at least one German cannibal.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Neither. Never Never Never Come Back was published by Salt Publishing in 2012. No agencies were harmed in the making of this book.

***

My writers to tag are:

1. Hong Kong-born poet, author of Summer Cicadas and Chinese translator Jennifer Wong

2. Leicester native, author of hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica and birdman Matt Merritt

3. Reportage poet, ukelele demon and Blake afficionado Jude Cowan Montague

4. International poetry evangelist, collaborative tinkerer and all-round alchemist SJ Fowler

Make sure you check them out on 2 January 2013!

The idea is I post mine and tag other writers to do the same on 2 January 2013.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

The title for Never Never Never Come Back came from the Al Stewart song 'Night Train to Munich', which adopts the voice of a senior agent instructing their colleague on an operation from which they may not return. I wanted my first collection to have the combination of paranoia and loneliness that plague the classic spy figure; distrusting everyone, under pressure to deliver something valuable without knowing why.

What genre does your book fall under?

Poetry

What actors would you choose to play the part of your characters in a movie rendition?

Many of them are actually based on films and programmes anyway - 'Supper' focuses on a scene from Soylent Green, 'Yokohama Shopping' on the anime series of the same name and 'Schoolgirl Shootout' on the tragic lighthouse blitz in Japanese thriller Battle Royale. Maybe Tilda Swinton for the metal ex-assassin in 'Roy'. I'd quite like to see Rutger Hauer play Armin Meiwes. Cillian Murphy would take on the more lovelorn, gawky characters, while the main role in 'On coming out to your parents dressed as Dracula' could only go to Sam Rockwell. I love that man.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Wheeling a broken bike through an embarrassing dream in which nobody else is naked, nobody else has forgotten their gift and everyone else knows the words to the song

How long did it take you to write the first draft of the manuscript?

Very hard to tell, though I think only one of the poems ('Splitting the ego with Mary') was more than two years old when we put NNNCB together. Most of the poems came from NaPoWriMo 2011 and 2012, which tends to dust under the corners of the brain where the weird stuff lies. The putting together and sifting of the poems took about six months with editor Roddy Lumsden.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

Everybody is under pressure to fulfill multiple roles at once, relating to this idea of a person they're advised to become. I wanted to probe the idea of breaking down under this brick-filled rucksack, of the ludicrous rules that can quietly destroy people. Poetry, with its restrictions, concentration of language, repetitions and cycles, seemed like the best form in which to explore this.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

A good helping of robots and at least one German cannibal.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

Neither. Never Never Never Come Back was published by Salt Publishing in 2012. No agencies were harmed in the making of this book.

***

My writers to tag are:

1. Hong Kong-born poet, author of Summer Cicadas and Chinese translator Jennifer Wong

2. Leicester native, author of hydrodaktulopsychicharmonica and birdman Matt Merritt

3. Reportage poet, ukelele demon and Blake afficionado Jude Cowan Montague

4. International poetry evangelist, collaborative tinkerer and all-round alchemist SJ Fowler

Make sure you check them out on 2 January 2013!

Tuesday 25 December 2012

I'm Walking Backwards (but looking forwards) for Christmas

Just a quick post to say thank you to everyone for a great year. Sidekick Books has had a tiring but good 2012, putting out the second part of our four-volume tribute to Britain's birds, Birdbook II: Freshwater Habitats, and the long-awaited print version of Simon Barraclough's Hitchcock tribute Psycho Poetica.

Whether you've written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

Whether you've written for us, illustrated for us, bought books, come to readings, evangelised about our strange schemes online or simply investigated the dark world of Dr Fulminare in passing, we appreciate it and will continue to provide characteristically Sidekick weirdness in 2013.

K x

Sunday 23 December 2012

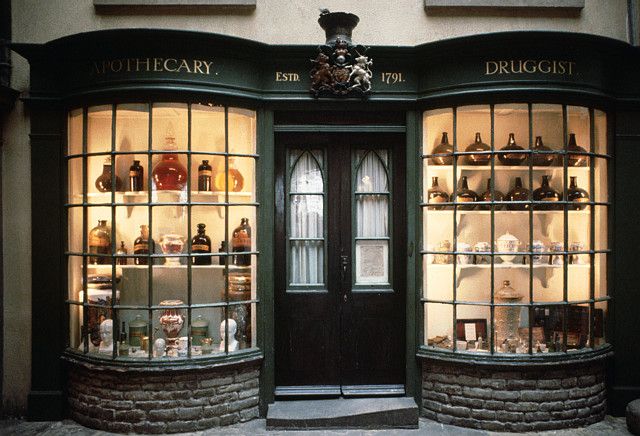

Sunday Review: The Apothecary's Heir, by Julianne Buchsbaum

posted by the Judge

The last Sunday before Christmas. A silent night, a holy night... no-one mentioned it was supposed to be such a COLD night.

To warm your spirits, here's some Baileys... nah, I kid, I kid. What I can give you instead is our Sunday review, which deals with Julianne Buchsbaum's The Apothecary's Heir. It's a pretty big deal, as it's been chosen yonder in the US of A for the National Poetry Series. Rowyda Amin, our specialist beyond the Atlantic, tells us all about it in the article.

What the heck, it's impossible not to close with these words. Merry Christmas everyone, and have a glorious 2013!!

Saturday 22 December 2012

Christmas Chiller

In a departure from my generally poetically-inclined endeavours, I've written a short five-part Christmas horror story, which will be serialised by Popcorn Horror over their smartphone/tablet app and website from 21-25 December. It's called Krampus Inc. How to summarise it? Well, suppose the European legend of a Yule devil were true, and he'd been taking tips from humanity in how to get his own way ...

Wednesday 19 December 2012

Losing the Poetry in 'The Hobbit'

The Judge takes a break from the series on poetry criticism to write something of an extemporary feature article - one which, be ye warned, contains a few spoilers. (The series will be finished, worry not, probably after Christmas).

Consider this poem by JRR Tolkien:

Where now are the horse and the rider? Where is the

horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the harp on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

Who shall gather the smoke of the deadwood burning,

Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the harp on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

They have passed like rain on the mountain, like a wind in the meadow;

The days have gone down in the West behind the hills into shadow.

Who shall gather the smoke of the deadwood burning,

Or behold the flowing years from the Sea returning?

It is marked by a rending sense of melancholy and nostalgia

for that which is past, and this nostalgia is expressed on many levels.

Firstly, it is literally stated, as the speaker rhetorically suggests that

nobody shall ‘behold the flowing years from the Sea returning’. Secondly, it is

rendered in the naturalist imagery that takes over from the classical one in

line three (nicely synthesised in the transition from the harp to the fire),

and which stands in contrast to the industrial world in which Tolkien lived.

Finally, it is implied in the choice of form and diction. Phrases like ‘Where

now are the horse and the rider?’ or ‘Who shall gather the smoke’ are

constructions which come straight out of classical poetry, much like the

alliterative style (helm – hauberk, harp – harpstring, days – down, etc.)

derives from poetry in Old English, from Beowulf onwards. Tolkien is invoking,

among other past ages, the past ages of poetry.

The poem comes from the

Lord of the Rings, and it encapsulates not only one of the book’s central

themes, but also one of its literary merits. Central to the enduring success of

Tolkien’s masterwork is the grace with which it brings together his differing

interests in lyric poetry, in epic poetry (the latter expressed in his famous

essay ‘The Monster and the Critics’ and, apparently, in an upcoming epic poem of his own), in philology, and of course

in the novel, a form which he first touched in The Hobbit.

Peter Jackson’s An

Unexpected Journey, released less than a week ago and already leading all of the charts, is the latest attempt to transpose Tolkien’s work to the big screen. Like

the Lord of the Rings trilogy, it is

a rather dreadful effort. Jackson’s passion for the text is unquestionable –

he’s certainly researched the source material. It’s his understanding of what

makes the books work, in particular their textual subtlety, or his ability to

translate that into a new medium, that is lacking.

An Unexpected Journey

is not as faithful to the book as the previous trilogy was. Indeed, Jackson has

taken the opportunity to make an out-and-out prequel, and the

differences between book and film have already been lamented.

What none of the reviews I’ve read have pointed out, for some reason, is the

gulf between Tolkien’s use of language and Jackson’s use of images – and this

is a problem that was already sharply on display in the original filmic

trilogy.

The primary difference between poetry and film is that one

is linguistic whereas the other is visual. But nothing prevents these media

from using words and image to produce the same effect. Jackson’s greatest failure lies precisely in reading the novels with

a purely literal eye. As a consequence, he is unable to reproduce levels of

subtlety such as we find in the above poem, even though he follows the diegetic

rails quite accurately.

Tolkien’s prose owes much to the Gothic novel, for the good

and for the bad. It is extensively descriptive, especially when it comes to the

journeying, and the diction is archaic – even a bit highfalutin. While it is

not always successful, the understanding that it belies remains one of beauty –

and it is a type of beauty that is delicate, subtle and transient. Jackson’s

imagery is entirely lacking in all of these qualities. His films are defined

by blazing dawns and sunsets, shots of intricate baroque cities framed in their

gigantomaniac entirety, crashing silver waterfalls with rainbows spearing

through them, and endless swoops over forests, rivers and mountains. When

important characters must be introduced, the image blares: the elf queen

Galadriel appears in this latest film with a blinding, golden rising sun behind

her as she turns in slow motion. When a dialogue is important, the visual

trumpets blow again (maybe that’s where that horn is blowing after all, John):

the final reconciliation between Bilbo and Thorin takes place during a sunset,

and all the characters are bathed in a refulgent light. Jackson in fact has

much more in common with the silver-maned George Lucas than he does with

Tolkien, in style and talent both.

Is this really a failure inherent in the category – be that

film, fantasy or blockbuster? Exactly thirty years ago another movie was filmed

in the very same genre. It too was a fantasy epic blockbuster, though there was

nothing epic about its budget. It was entitled Conan the Barbarian, and it was a film dominated by the titanic

physical presence of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his prime. It wasn’t nearly as silly as people usually remember it to be, and more importantly, it had

exactly what Jackson’s films are lacking: a visual style that is frequently and

essentially poetic, if in a bleak and barren way. Director John Milius opens

the scene of Conan’s crucifixion on the ‘tree of woe’ (see it for yourself at

minute 3:57 of this video) with a wide angle, giving us a clear view not only of the tree but of the

desert that surrounds it. The wide angle implies the epic breadth and scope of

the story, while the monochrome desert reflects its crude simplicity; the

solitary, leafless tree mirrors Conan’s sense of spiritual isolation. The frame

fades out into the desert, then pans onto the hero’s ravaged physique,

reinforcing the thematic connection between the two. The scene has tremendous

suggestive power, and not a single word is spoken.

Compare the tree of woe with the moment in The Hobbit when Thorin rises from his

own tree, the one where he has been pinned down by his enemies’ hounds. As he

goes to fight his rival, he is hit and he falls. As he falls, events start

rolling in slow motion. Then a track of violins starts playing. When Thorin

hits the ground, the frame cuts to a close-up of a dwarf shouting ‘Nooo’, and

then back to Thorin. It is such a standard form that it is almost scholastic;

there is no space for imagination, sentiment or suggestion. It is as though

Jackson automatically assumed that his audience was comprised of idiots, so he

does not trust them with feeling or understanding anything on their own.

Instead, he gives them small cues to indicate them when to feel sad, when to

feel relieved, when to feel worried. Imagine Tolkien being that explicit in his

poem.

There are many other flaws in Jackson’s films. The action

scenes are terribly choreographed, there is an over-reliance on CGI which only

Lucas is able to match and which is not very competently used (I was unable to

find a single creature which looked alive,

not even the simple ones like hedgehogs and birds), and the characters are

mostly quite flat, including the inescapable, odious comic relief – in this case

an obese dwarf, because as we all know fat people are funny. But the one thing

that really crumbles the connection between these films and the original texts

is simply the vulgarity of Jackson’s direction. Even when inserting the poem at

the top of this article in one of his character’s monologues (one of the few

fine moments in the films), the use of light is almost blinding.

For Tolkien, like for the great epic poets, the golden age

is a thing of the past, necessarily and inherently irretrievable. For Jackson,

the golden age is right now – and it’s getting more and more golden as the

increased powers of CGI allow for brighter dawns and sunsets in higher definitions and frame-rates. Jackson certainly appreciates Tolkien’s poetry. The problem, judging by this

film and the ones that came before, is that he doesn’t understand it.

Sunday 16 December 2012

Sunday Review: New Scottish Poets Anthology

posted by the Judge

It's Sunday!! This means two things for me. Firstly, I'm going to be putting up our Sunday review. Secondly, I'm going to try and take a certain girl to the cinema, probably to see The Hobbit (which I expect I won't like, but I like the girl, so let's just give this thing a chance, eh?).

Regarding the review, we are dealing with the New Scottish Poets Anthology, edited by Sandra Alland. Find the review by clicking on this link. Our critic for the occasion is Harry Giles, himself a son of Scotland, whom you can see in the photo above as he meditates on the review (he doesn't look Scottish though).

Enjoy your Sunday, enjoy the review, and I'll try and enjoy The Hobbit.

Wednesday 12 December 2012

The Poetry Critic and the Consumer (On Criticism #2)

written by the Judge

Criticism in most art-forms or media other than poetry is

informed by at least two opposing registers. On one hand, it is concerned with

the interpretation and elucidation of a text. On the other, it functions as a

consumer guide. Just like the review of a car, a cruise company or a mobile

phone, criticism of film, music, novels, comics and games is often concerned

with letting the reader know what product they are about to invest their resources

on. Is this movie worth my money? Is this music album the right type of gift

for my girlfriend? Is this game something I can let my ten- and twelve-year old

children play? Criticism will usually balance the ‘intellectual’ and the

‘consumer guide’ (CG from here) registers depending on how these two are balanced

in the medium itself. Film reviews usually lean towards the CG,

reflecting the fact that the most popular movies in terms of sales are

commercial blockbusters; but they have a very powerful, firmly established institutionfor intellectual criticism as well, catering for the interests

of the numerous viewers who are passionate about film-making as an art. Games,

which are the youngest medium, never developed such a thing as an intellectual

criticism until only very recently – and the release of triple-A titles

continues to correspond to (mostly) homogeneous responses from the critics.

Poetry criticism is idiosyncratic because, even while

sharing the first role of interpretation and elucidation, it lacks the CG

register entirely. The question of whether a poetry collection is ‘worth your

money’ is never seriously posed, and there are no concerns in terms such as

parental control. Furthermore, most readers have already made up their mind on

whether to buy a book or not before they read the review (often they will come

to the review as a way of following up on reading the book itself). Word of

mouth goes a much longer way towards popularising a collection than the

established magazines and webzines for poetry criticism. Even when a reader is in

doubt, the typical strategy is simply to look for poetry samples, rather than

reviews. These can normally be found online, and they give a much better idea

of the text than something like a trailer or an album’s single could ever hope

to do.

Though these are, I think, realities of the poetic scene

that most people are familiar with, newcomers to criticism (and sometimes not

them alone) are still more likely to be troubled by the absence of the CG

register than by anything else. We say this bearing in mind that, in a world as

shifting and unstable as that of poetry, ‘newcomers to criticism’ are anything

but a small or unimportant group.

Greener critics still approach the writing of a review as

though its main purpose were to answer the question ‘Is it good?’ This is

understandable, because it’s the question which seems to be at the heart of

most other criticism out there. Unfortunately, it only really makes sense when

there is a CG register behind it. ‘Is it good?’ can be translated in several

manners according to the product – it can be a different way of saying ‘is it

worth my money?’, or ‘does it work?’, or for more intellectual groups, ‘does it

promote a set of values we approve (feminism, pacifism, liberalism, etc.)?’

On the other hand, what does it even mean to say that poetry

is ‘good’? There is no consensus on the subject, no standards to appeal to.

There is no Rottentomatoes.com to tell us what the critical community thinks as

a whole. There’s barely any way of measuring popularity by sales, which at

least provides one type of response. If anything can be said with confidence at

all, it is that the criteria for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ – in terms of how they can be

relevant to a piece of criticism – are completely different in poetry than they

are in other arts. I would go further than that and say that they are

irrelevant, and that critics should not be posing that question at all when

approaching a collection. Praise along the lines of ‘this poet shows real

confidence in his / her diction’, or criticism like ‘some of his / her formal

poems are weaker than the others’ is generally giving sterile information. So

this guy’s syntax is clever – so what? Where do we go from there? What is the

point of reading this? What is there to discuss, other than personal taste?

This is information that the reader was probably not looking for and that, by

and large, s/he does not care about. Remember: the reader has, in all

likelihood, either already read the book or already made up his / her mind as

to whether to buy it.

The real question that should inform a poetry review is

‘What is it saying?’ Or, alternatively, ‘What is it about? What is it really about?’ In a form of art that is

almost entirely built on subtlety, allusion, metaphor, reference and double

meanings, this is the one question that is always imperative, and that can

never be taken for granted.

Note that I specifically said ‘What is it saying’ and not ‘What is s/he

saying’. Though the most academically versed of my readers may roll their

eyes and take this for a given, it’s always important to state that a poem

speaks for itself, independently of the poet’s intention. Interpreting a poem

is not an act of archaeology directed towards a hypothetical urtext held inside

the poet’s head. Instead, it’s about letting the poem open up and speak for

itself, in ways that even the artist may have been unaware of (this is easier

to understand when the interpretation is negative – if you are describing a

poem’s failings, you are pointing out questionable statements and internal

contradictions that the author likely did not intend; the act of interpreting a

poem positively should be seen as essentially no different).

The poetry critic is responsible for providing an engaged

and researched interpretation for a reader who may only have skimmed through

the poems casually, or may not be familiar with the context or cultural objects

treated in the text (for instance, the reader may come from another country, or

even be new to poetry altogether). People who dislike a collection may simply

not understand it (sometimes, even those who like a collection may do so without knowing why). The poetry review

should be the first place where they can turn to find someone to help them out.

In this sense, a review functions a little like an introduction that is

published outside of the book.

At the same time, however, the poetry critic meets in the

question ‘What is it saying?’ a responsibility that is more profound than that

of the mere introduction. To the extent that poetry is its own scene, environment

and (sub)culture, it also carries with it its own prejudices, biases and

misconceptions. There are myths – within, not only outside of the culture –

that mischaracterise the poet, the reader, the media, the history, or even

individual figures and movements. Sometimes poets come with ideological

agendas, determined by their class, their culture and their background. It is

the critic’s job, then, to identify and question specifically those discursive tropes in a poetry

collection which are particular to the world of poetry.

Though we ideally assume that reading poetry always frees

and expands our minds, there are ways in which it can do the opposite (and

this, I would argue, is the only case in which we can legitimately talk about bad poetry – a matter which has nothing

to do with technique, emotional impact or beauty / lack thereof). Lofty

embellishments aside, poetry is still fundamentally one person expressing him /

herself through language. And like any other mode of expression, it can and

will be weighed down by the speaker’s own conceptual and cultural limits. I

make an extreme example: a racist individual writing a poem will likely reveal

his / her bias in the choice of words and imagery, and this will often be the

case even if the chosen topic has nothing to do with ethnicity (if this does

not hold true of an individual poem, it will for a full collection). The

case-study is implausible – anti-racism is pretty much taken for granted in

poetry circles. But what are the values that are not taken for granted? Racism is something that is easily

recognised (and rejected) by the poetic groups because it comes from outside the subculture – but what

of those beliefs and ideas that are particular, if not exclusive, to the

subculture itself? For example, what do we consider the role of art to be in

society? Are we all on the same page? Is anyone right and anyone wrong? More to

the point – could our views on art be discriminating certain groups or types of

artists? Could they be promoting a perspective that is in any way hegemonic, for

instance by pressing the view that a poet should be doing or saying particular

things, belonging to any given class or group, or that s/he should behave in

certain ways in (relation to) society? Does a poetry collection in/directly

promote a political agenda, and does it thereby imply that poets in general

should conform to this agenda? Is this

a form of discrimination that we are genuinely trained to recognise and not

tolerate?

I am making examples that are generally ‘ideological’ in

nature, but they don’t have to be. Any interpretation of the text that is aware

of how the text derives its power and slant from its medium, its sub/culture,

or its institutions will be answering the question ‘What is it really saying?’ Here

are some more examples: how does the fact that an opinion is written in a poem affect our reception of that

opinion? What are the themes or statements that typically appear in poetry as opposed to other forms of expression

– and why are they so typical of poetry? What is it that makes them ‘poetic’?

How, and how aptly, does poetry give a voice to minorities? What are the forms

of minority discourse in poetry, and how is our response to this discourse

different in poetry than it is when we encounter it in other media? And how do

‘minority’ poets in turn reflect these poetic expectations in their verse? Where

does poetry come from, i.e. which social groups produce poetry and operate its

forums – is there a pattern? – and how does their background reflect itself in

the verse (we have asked this question, for example, of academics)? How is poetry represented by the greater media

and popular culture, and how does this representation in turn affect poetry’s

own understanding of itself?

These are exactly the kind of issues that a poetry critic

has a responsibility to address, and which define his / her job as something

quite different from that of the film critic, the game critic or the music

critic. Poetry is not an Olympus of intelligence and sensitivity; it has its

own discursive, formal, ideological limits which clamp it and its interpreters

down. Recognising and pointing out these limits, so that we may all move beyond

them, is the job of the critic. And if this sounds difficult or complex, you

are probably reading too much into it. It is enough, when approaching a

collection for a review, to ditch all the questions of whether it is good or

bad or average or whatever, forget the useless mystery of what the author may

have intended, and simply keep asking yourself while reading: ‘What is it

saying? What is it really saying?’

(Part three coming next week, fellas. We're not done yet).

Monday 10 December 2012

Psycho Poetica gets a Telegraph mention!

Psycho Poetica, editor Simon Barraclough's multi-poet love letter to Hitchcock's classic, was mentioned in the Telegraph today, in a round-up entitled 'The best recent poetry'. That sexy, skinny volume snuggled between Poems on the Underground and Josephine Hart's Life Saving? That's us! Nice quote from Isobel Dixon's 'Trappings',

Image copyright The Telegraph, 2012.

Labels:

Isobel Dixon,

poems,

poetry,

Press,

Psycho Poetica,

Sidekick Books,

Simon Barraclough,

Telegraph

Sunday 9 December 2012

Sunday Review: Waterloo by JT Welsch

posted by the Judge

Sunday review, fellas!! And the reason Napoleon is so angry, is that this review is about Waterloo (but the one by JT Welsch, so I guess that's ok). The review was written by Anthony Adler, who makes a happy return to our virtual pages.

Even though when I hear of Waterloo I always think about this particularly inspirational speech by a luminary of Telecom.

Have a great Sunday!

Sunday review, fellas!! And the reason Napoleon is so angry, is that this review is about Waterloo (but the one by JT Welsch, so I guess that's ok). The review was written by Anthony Adler, who makes a happy return to our virtual pages.

Even though when I hear of Waterloo I always think about this particularly inspirational speech by a luminary of Telecom.

Have a great Sunday!

Friday 7 December 2012

Where Rockets Burn Through!

If you're stuck for a gift for the sci-fi fan in your life, and a slogan t-shirt isn't going to cut it, Penned in the Margins might just have the answer.

New anthology, Where Rockets Burn Through: contemporary science fiction poems from the UK, is not only beautifully designed (Sunstreaker and Wheeljack seem to think so, anyway) but also makes for a laser-firing, catsuit-sporting blast-off of a poetry mission.

Jon and I pop up a few times inside (he re-jigs Catullus into space opera while I salivate over the precious meal from Soylent Green), alongside some seriously spark-spitting other writers.

Gifting poems to those who are usually more fond of box sets than tercets may seem like a risky gambit, but editor Russell Jones has picked a rich range of moreish work that, while intriguing and substantial, won't alienate (apologies for that one) anyone coming to poetry afresh. Poetry has a knack of providing an off-kilter, probing new look at classic tropes and well-loved stories, and this is a real genre-zapper.

Where Rockets Burn Through: contemporary science fiction poems from the UK is normally £9.99 plus p&p, but until 21 December, Penned are offering 20% off,so you can snaffle it for £7.99 plus postage.

New anthology, Where Rockets Burn Through: contemporary science fiction poems from the UK, is not only beautifully designed (Sunstreaker and Wheeljack seem to think so, anyway) but also makes for a laser-firing, catsuit-sporting blast-off of a poetry mission.

Jon and I pop up a few times inside (he re-jigs Catullus into space opera while I salivate over the precious meal from Soylent Green), alongside some seriously spark-spitting other writers.

Gifting poems to those who are usually more fond of box sets than tercets may seem like a risky gambit, but editor Russell Jones has picked a rich range of moreish work that, while intriguing and substantial, won't alienate (apologies for that one) anyone coming to poetry afresh. Poetry has a knack of providing an off-kilter, probing new look at classic tropes and well-loved stories, and this is a real genre-zapper.

Where Rockets Burn Through: contemporary science fiction poems from the UK is normally £9.99 plus p&p, but until 21 December, Penned are offering 20% off,so you can snaffle it for £7.99 plus postage.

Wednesday 5 December 2012

Aspects of the Poetry Review (On Criticism #1)

written by the Judge

Attempts at describing any mode of criticism must account

for the fact that said criticism will always be shaped by the object which it

describes. Thus the critical industries behind film, music, literature and

gaming are shaped in a way that reflects the industries of those same media and

art-forms. It is exceptionally hard to speak of such a thing as ‘general

criticism’; the review of a concert will of course differ from the review of an

art exhibition in a way which reflects the (potentially incompatible)

differences between the two arts.

Accounting for poetry criticism must therefore take into

account the particular aspects that distinguish poetry from other arts – and

there is probably no better point to start from than the fact that, as we all

know (and at times lament), there is no money in poetry. There are what one may

call superstars in the subculture, but their status is more likely to be

measured by the number of times their names are mentioned in articles rather

than by the number of cars in their garage.

The fact that there is no money in poetry comes with several

important consequences; for one thing, it has an enormous effect on the form of

poetry criticism. Lacking the sponsorship to make a living out of reviews and

articles, critics can only operate out of passion and personal interest,

balancing these activities with their everyday needs. This poses a number of

challenges for any would-be editor: it becomes exceptionally hard to assemble a

group of reviewers working together for the same platform – their specific

interests and desires being driven by personal curiosity, they are less willing

to conform to editorial rules and standards than someone who is paid to do so.

Even harder than setting up such a hypothetical platform is the task of

sustaining it for an extended period of time; any event in the personal and

professional life of a critic could potentially draw him / her away from this

type of voluntary work. Many would-be critics in fact start out writing enthusiastically,

only to find after two or three of these unrewarded reviews that they do not

have as much time as they expected to keep doing this on the long run. Even

assuming a stable critical platform can be set up, it is hard to endow it with

a stable critical voice – too often its members will simply come and go,

meaning that the opinions and ideas held therein will change very quickly. Needless

to say, the inherent instability of any critical platform means that

communication between different platforms will be even more volatile.

In brief, the primary challenge posed to those who would

approach poetry criticism, either as writers or as simple readers, is the lack

of a cohesive, unitary critical voice or referent. Instead, the newcomer is

faced with a variety of sources, each operating according to its own terms and

by its own standards (and often unstable enough that even its own internal

standards will demonstrate inconsistencies and variations).

This is a direct reflection of the status of poetry itself,

at least as opposed to other arts. There are no stable critical platforms

because the artistic platforms themselves are considerably weaker and

disjointed. There is no such thing as an MTV, in poetry – a centralised space

that distributes poetry according to a democratic sweep of the consumer base.

Instead, there is a kaleidoscope of small and smaller independent presses,

almost unfailingly run by poets, working in a very intimate relationship with

their main artists. The world of poetry is fragmented into small social circles

interacting with each other in a way that is unique to the art – and criticism

is correspondingly fragmented into even smaller social circles, corollary to

the ones above.

It is true that there are some presses which are larger and

more powerful than the others (Faber and Picador stand out in the UK), and

whose publications tend to make waves. But they too depend for their criteria

on selected (if relatively wider and more prestigious) social circles, as

opposed to consumer response in terms of what’s selling. It is very rare for a new

collection published by Faber and Picador to earn a critical reception that is,

on the whole, negative, and this for the simple reason that the press and the

critical platforms are very closely interwoven (not, mind you, in the sense

that the critics are ‘corrupted’, ‘bribed’ or dishonest in any way – only that

they belong to the same social group as the editor and poet, and are thus more

likely to share in the aesthetic taste). In addition, there is no such thing in

poetry as that phenomenon we sometimes see in other arts, when a product sells

enormously but gets bashed by the critics (or vice versa). The consumers and

critics are pretty much the same, in poetry, so good sales (in relative terms)

will correspond to good reviews.

One important piece of evidence demonstrating the lack of

unity and agreement in the voice(s) of poetry criticism is the absence of such

a thing as a ‘scoring system’. Though the notion of grading a poetry collection

with numbers from one to ten or with percentile scores may appear ridiculous,

there is a reason we don’t have it – and this is not that the critics have all looked

at each other, shook their heads and said, ‘No, what a silly notion’. Bad

ideas, however bad, tend to have at least one or two practitioners, especially

in the universally democratic field that is represented by the internet. (That said, I would not be surprised were I now to receive an e-mail linking me

to some fellow who reviews poems and gives them numerical scores; the internet is

indeed a cavern measureless to man and I can only apologise for not having explored

all of it).

No, the reason there is no such thing as a scoring system is

simply that poetry criticism is unable to support it. The idea of quantifying

merit is just as good or bad for any other art as it is for poetry; if you

cannot do it for a pamphlet of verse, then you cannot do it for a movie either.

But scoring systems abound in the world of film, even in some intellectual sites, simply because there is such a thing as a common

language for criticism. This doesn’t mean that everyone speaks from the same

voice; but it does mean that (almost) everyone understands where others are

coming from. It is quite clear whether a site (or a writer) is dedicated to an

intellectual analysis, a consumer guide, a casual blog or even that peculiar

but surprisingly established genre of comedy criticism. These modes of criticism are all consolidated because the film

industry is equally well-ordered, as movies are accurately divided by genre,

target audience and production value. Imagine doing the same thing with poetry.

Think of the last five poetry books you have read or purchased, and try placing

them in a genre. Or, try defining the mainstream modes of criticism behind

poetry. (The challenge is rhetorical, but if you can indeed do that – then we want to hear from you!)

A scoring system would in fact be practical in many ways –

its purpose, after all, is never to evaluate a work of art, but simply to

provide common terms of discussion across critical platforms. But if the whole

thing is to have any meaning at all, you need to get your critics to all agree

on the criteria for the scoring rates, and give them the time to refine their

judgment according to those same criteria. As we mentioned above, gathering such

a durable assembly necessitates criticism to be a paid profession, and not a

(very noble) hobby. A scoring system could only be practiced with consistency

by someone writing alone, but (again) if that person is not paid, s/he is

unlikely to be able to review more than one book every three weeks (which is

not very much). And even then, how long can that person go before life gets in

the way and the output is cut short?

The subculture of poetry compensates for the lack of a

compass point in its criticism thanks to an exceptionally high level of

preparation in its readers. The ratio of reader per critic (or artist) is

probably lower in poetry than in any other art. In fact, almost anyone who

reads contemporary poetry habitually is qualified, at least potentially, to be

a poetry critic. This means that the reader of a poetry review will in

principle be equipped to understand and contextualise the review with no need

for an established source. It also means, however, that the critic must have

some special standards in terms of how to write the article. The readership is

different than what it is for a film or a game, and the review must account for

this difference, respond accordingly and then take responsibility for the way

said readership may respond.

What are these ‘special standards’? Having established some

of the ways in which the form of the poetry subculture influences the form of

its criticism, I now find that space is coming short. This doesn’t mean that I’m

going to cut the argument short, only that I’ll have to continue it next week. In the upcoming month Drfulminare.com is going

to publish a few more articles dealing with poetry reviews themselves, with

what makes them unique as items of criticism, and with the special

responsibilities of the critic in this particular context. See you next

Wednesday.

Part Two is out! Read it here!

Part Two is out! Read it here!

Sunday 2 December 2012

Sunday Review: Penned in the Margins round-up

A special Winter round-up this week - with yours truly back in the critic's seat! I know! It's been forever! Anyway, it's time to look over at fellow London published Penned in the Margins and assess the good work they've been doing in bringing bright, young poets into print. Click here to read on.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)